Go

to the Prior Tip Thinking, Fast

and Slow

by Daniel Kahneman

Go to the Next Tip The Black

Swan by Nassim Taleb

Go to Tip 094

Fooled by Randomness by Nassim Taleb

Return to MaxValue Home Page

Nassim Taleb in one of my favorite authors. Hands-down, he gets my nomination as the person best-qualified to handle financial system reform ... in the U.S. and elsewhere. I've been directing my colleagues to a posting of "Ten principles for a Black Swan-proof world" from the Financial Times (Apr 7, 2009).

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/5d5aa24e-23a4-11de-996a-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2OPMK6JmM

If the FT link does not work, try this:

http://globalguerrillas.typepad.com/globalguerrillas/talebs-rules.html

(I agree with most of his prescriptions.)

Antifragile is Taleb's central work, though he didn't recognize that his efforts to understand volatility would lead him here. There are two predecessor books. Fooled by Randomness (2001, Tip 094) led to The Black Swan (2007, Tip126). These earlier books were "written to convince us of a dire situation."

A lifelong scholar, Teleb is arguably the smartest person on the planet. Since 13, he has been a prolific reader spending 30-60 hours each week in self-directed study. The books he loves best have stood the test of time.

As Taleb sees it, his duty as a scholar is to write books. Books represent a store of learning and a key mechanism for improving society's DNA. Since writing The Black Swan and through writing Antifragile he has spent more than 300 days a year mostly in extreme seclusion. Taleb says most conventional information is just "noise." He isn't much interested in an idea unless it has survived at least five years of scrutiny. Many of the best ideas came from the ancients.

Fragility: Many, if not most, systems are supposedly optimized in design. Governments, corporations, and people get the most attention in the book. They are vulnerable to changing conditions. Fragile systems suffer from volatility, often in dramatic ways, such as bankruptcy or death. Fragility can be measured, and we should expect highly-fragile systems to fail.

Projects tend to be fragile. When things start to go wrong, problems typically multiply and cascade. Task completions times are bound by some minimum at the low end and have no upper bound. The "planning fallacy" (project times and costs are underestimated) have long been attributed to over-confidence and over-optimism in estimates. Information technology is perhaps the major culprit (p. 285). We optimize the project plan with parallel activity paths, modeling in ever-increasing detail, and frequently reporting progress. Yet we're not very good at forecasting. (My note: We are getting better at modeling projects. Monte Carlo simulation models can represent contingencies and cascading effects. We can incorporate rework cycles. Merge bias (a.k.a., stochastic variance) explains the effect of uncertain predecessor completion times on task start time.)

The U.S. expected the Iraq war to cost $30-60 billion. "Indirect costs multiply, causing chains, explosive chains of interactions, all going in the same direction of more costs, not less (p. 286). So far, recognizing direct and indirect costs, the war cost may have swelled to more than $2 trillion. This project was bound at the low-end and is (yet) unbounded at the high end.

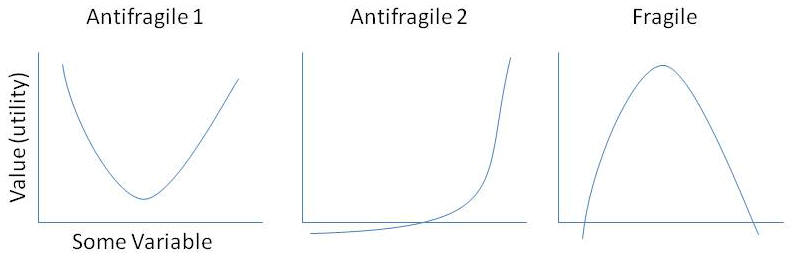

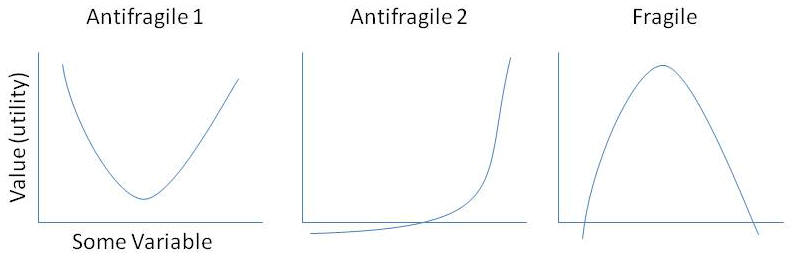

Antifragile: The characteristic of a system to benefit from volatility. Some financial contracts are expressly designed to benefit from market volatility. In the figure below, the left two charts are convex (as viewed from below); these benefit from volatility. The concave curve at the right represents a system that is harmed by volatility.

Debt is a fragilizer. Most financial crises have excessive debt as a root cause. (see Tip118)

However, perhaps "the largest fragilizer of society, and the greatest generator of crises, (is) absence of 'skin in the game.'" Government officials, rogue traders, investment bankers, and others are incented to take big risks. These managers often have huge upside yet little downside exposure (antifragile 2 in the figure).

The chief ethical rule: "Thou shalt not have antifragility at the expense of the fragility of others."

Black Swans: Taleb claims that Black Swans—rare, unpredictable events—caused most of history. As these are unpredictable, the best we can do is make our systems robust (not fragile) or, better, antifragile.

The Fragility-Robustness-Antifragility triad: This classification is useful, though actually it is a continuum. Taleb says the idea for the triad was born in 2009 at a conference in Korea. A presenter was showing his department's economic projections for the next four years. Knowing that projections are usually far apart from what actually happens, Taleb was outraged at the presenter's confidence in the projections. Taleb says, "I ran to the podium and told the audience that the next time someone in a suit and tie gave them projections for some dates in the future, they should ask him to show what he had projected in the past (p. 135)."

Note: I find it helpful to distinguish projection from forecast. As we use these terms, projection represents a deterministic (what-if) case. In contrast, forecast represents a an opinion, usually calculated by probability-weighting possible projections.

"You decide principally based on fragility, not probability (p. 260)."

Taleb despises probabilistic decision making, i.e., decision analysis (DA). I take strong exception. The most important management responsibility is capital allocation (as well as other resources). Forecasts are necessary. Decisions must be made, and DA allows us to the best we can with what we know. Lessons from Taleb include: use history, lessons learned, and reality checks; don't let quantification lead to overconfidence in risk taking; and design solutions to be flexible and robust in the face of uncertainty.

Here's a scary thought: "A war that would decimate the planet would be completely consistent with the statistics, and would not even be an 'outlier' (p 98)."

Other Interesting Ideas

There are so many. Here's a sampling:

We overestimate the value of scientific knowledge. Most new ideas fail with time. Much of what has been learned across millennia is captured through generations as traditions, heuristics, and craft trades.

Systems and people become brittle in a stable environment. Ease and comfort will be punished later. It is helpful to provide systems with occasional stressors. Then the system typically overcompensates and becomes more resilient. For example, government bailouts: these transfers fragility from the collective to the unfit. It is better for the collective to let the weak ones die out. Ruthless selection of those members that overcompensate without failing (p. 48).

Trying to optimize the economy and smooth-out business cycles leads to more severe crashes when they inevitably happen.

When talking about individuals, Taleb admits that he struggles with a serious conflict. Nature is ruthless with selection. However, Taleb believes in mitigating harm to the very weak (p. 75, 77).

Most of human progress is made by unsung heroes.

Taleb elevates the entrepreneur and tinkerer: most will fail. Most

discoveries have been made by amateurs using trial-by-error. Thomas Bayes

(Bayes' rule) was an example of en enlightened amateur mathematician (p.

224). Little progress is made by governments funding directed research.

"Sophistication is born of need, and success of difficulties (p. 203)."

"Romans, admirable engineers, built aqueducts without mathematics." They

were not engineers, in the modern sense, but rather craftsmen applying

construction methods and heuristics passed-down through generations.

Switzerland is perhaps the most antifragile place on the planet. It benefits from shocks elsewhere in the world. It is stable because it does not have a large central government. Local mini-states make up a confederation. Lobbyists (mutant scourges) are ineffective at local levels. Small states are not tempted to engage in wars.

A Legal Way to Kill People: "If you want to accelerate someone's death, give him a personal doctor." The doctor will attempt to treat most any symptom. Doing nothing is unacceptable and possibly malpractice (the legal system favors intervention, p. 345). Physicians are incented to treat, where nature alone will normally cure the patient. Most symptoms are just noise, anyway.

One antifragile strategy is to bet against fragility. In the fall of 1990, the U.S. was preparing to invade Iraq to restore Kuwait. This war was scheduled, and most everyone was anticipating (there's the fragility) an oil price rise in the event of war. Oil price forecasts adjusted to this belief. A friend of Taleb's, "Fat Tony," saw opportunity in betting against the crowd. Indeed, instead of oil price rising it fell on the news of war start. With the price collapse, Tony's $300k investment turned into an $18 million profit (p. 210). Antifragile 2 in the figure is an approximate illustration; huge upside, modest downside.

As you've gathered by now, I think this book is marvelous. Taleb enlightens and provokes the reader. This is not casual reading. I recommend having an Internet browser nearby to look up word definitions and historical figures.

—John Schuyler, Mar 2013

Copyright \A9 2013 by John R. Schuyler. All rights reserved. Permission to copy with reproduction of this notice.